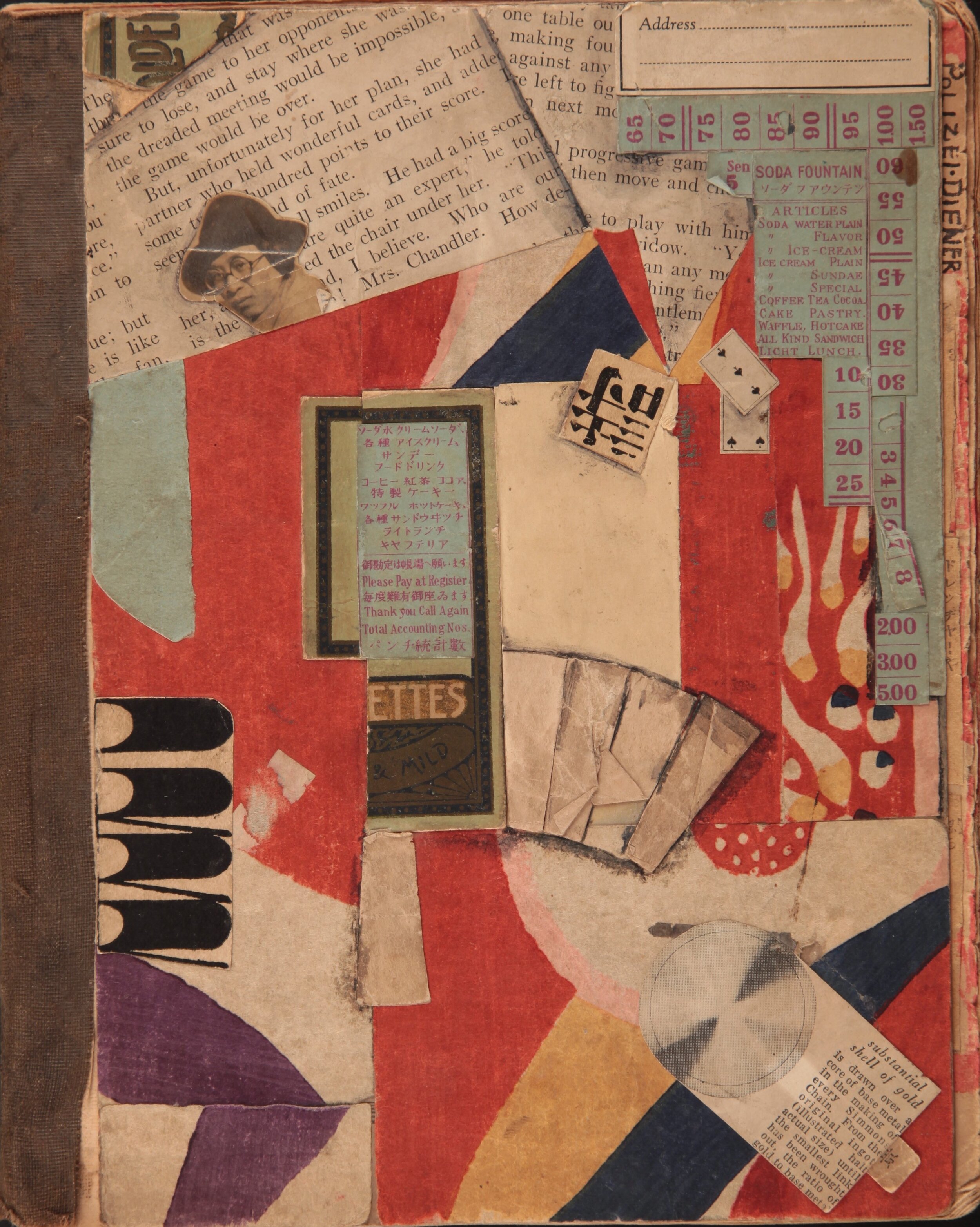

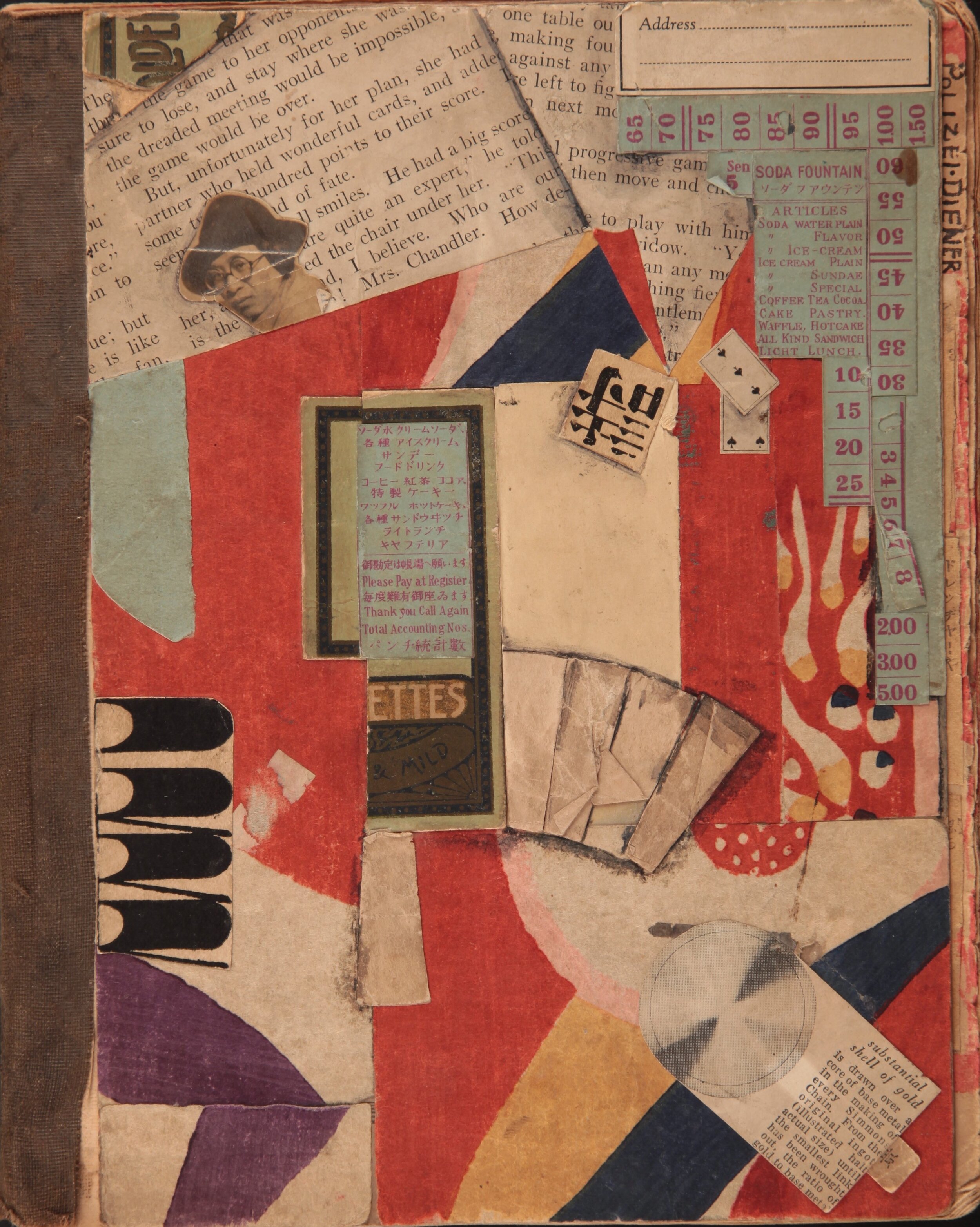

Containing Kitasono’s early journalistic work, this scrapbook was created in the midst of his engagement with Dada and the magazine Ge.Gjmgjgam.Prrr.Gjmgem (1924-1926). Along with collaged papers from multiple sources, including lettering from the magazine, its cover features a small photographic portrait of the poet. Though the work is of an early date, the collage’s use of mixed media, abstraction, and assemblage, as well as its engagement with multiple languages foreground themes that would occupy Kitasono throughout his whole life.

The poetry of Kitasono’s first book, Album of Whiteness (1929), while written under the influence of Dada and the nascent Japanese surrealist movement, is thoroughly unlike the avant-garde poetry common at that time either among his milieu or among the mostly French poets from which it had originated. Rather, it sets out—inspired by these movements but not limited by them—towards new procedures, forms, and usages of language.

Including diagrammatic poems (Legend of the Airship), proto-concrete poems (Magic), and poems of ironic and extreme imagistic minimalism (Semiotic Theory), the work in Album of Whiteness seems to look far-ahead to movements of the future, from visual poetry to language poetry and text-based conceptual art.

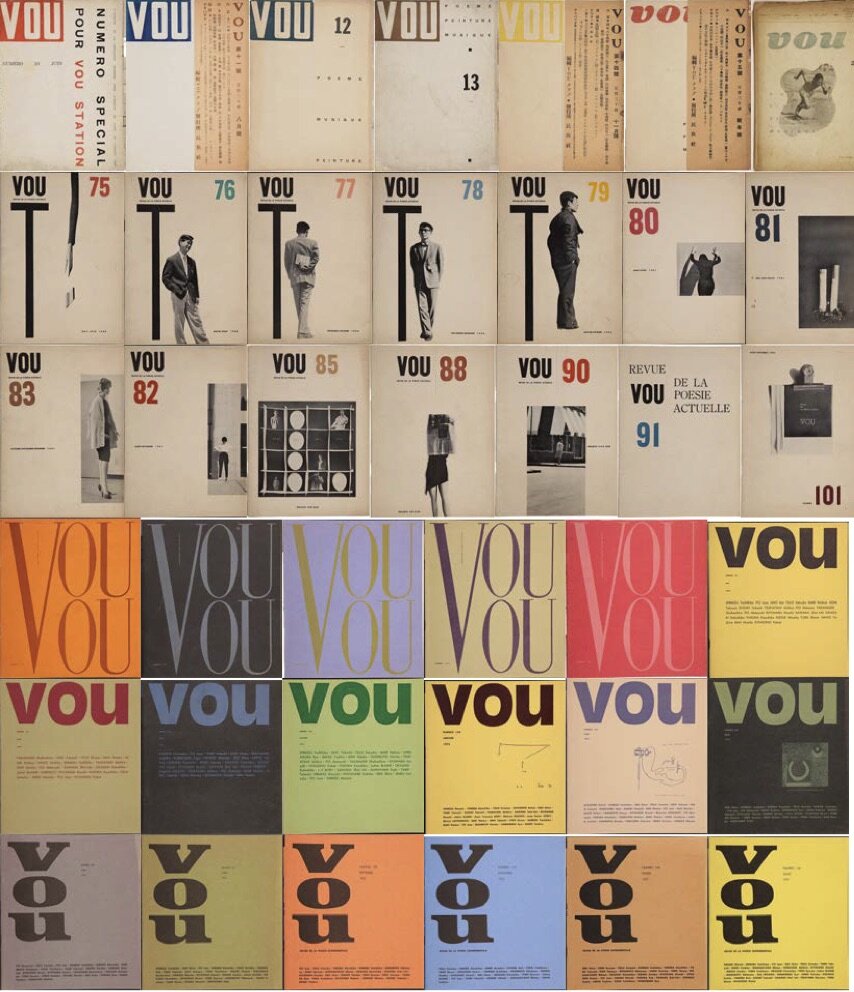

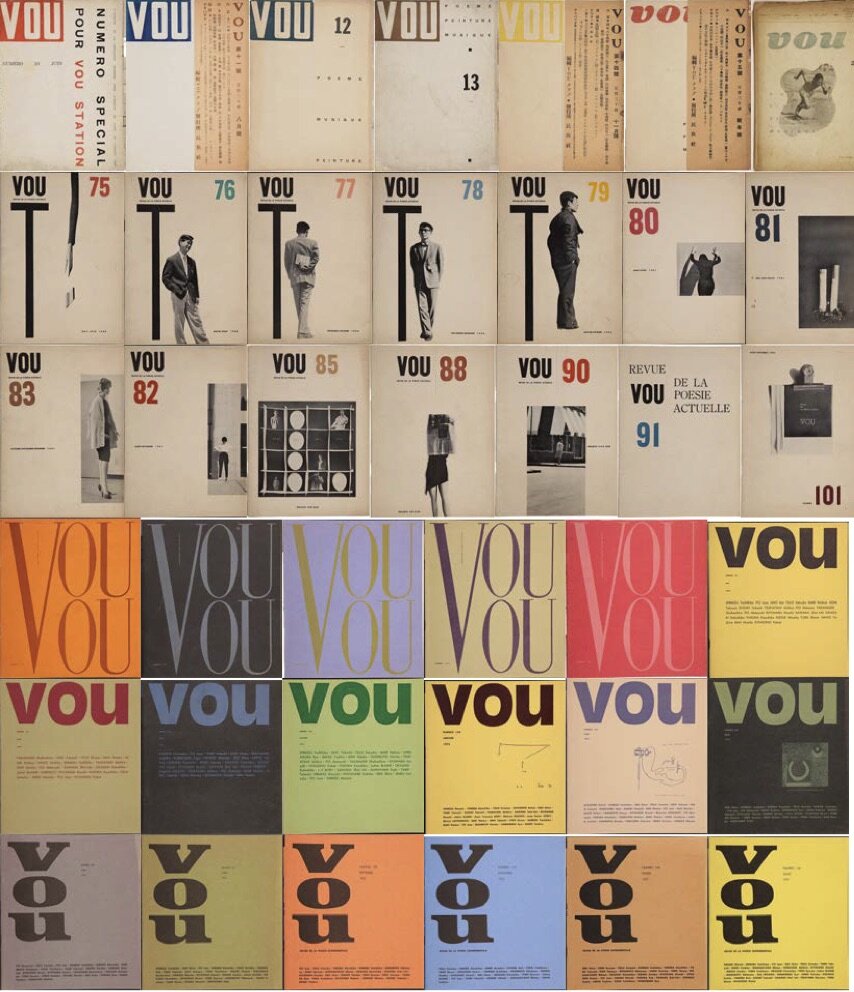

VOU magazine’s innovative formal concerns, its long life, and Kitasono’s ability to reach across culture and disciplines, made it one of the most widely known and influential non-western avant-garde magazines of the 20th century.

While there were several important avant-garde publications in Japan during the pre-war period, few were in touch directly with individuals outside Japan, and most, like MAVO and Kitasono’s own Madame Blanche or Ge.Gjmgjgam.Prrr.Gjmgem, lasted only a few years. VOU, on the other hand, starting in 1935 and ending in 1978, was the only major group and magazine to span the pre- and post-war. Additionally, it engaged directly with international artists on a large scale, facilitating translation and dialogue with nearly every major avant-garde group of that time, from the Surrealists to the Black Mountain School, Beat poets, and concrete poets.

Edited and designed by Kitasono Katue, his prints and photographic works often appeared on the covers, a small selection of which are pictured above.

A small collection of images from VOU can also be found on the plastic poetry page of this site.

Kitasono corresponded with many western artists and poets, but his most sustained engagement was with Ezra Pound, their dialogue beginning in the middle-1930s and lasting approximately three decades.

Though there were difficulties of language on either side, Kitasono and Pound’s letters served as a sounding board for their respective poetics, and are marked by mutual respect and collaborative assistance on both sides. Pound was instrumental in Kitasono and VOU’s publication in the west, and Kitasono in Pound’s publication in Japan. Pound explored Kitasono’s poetics in his influential Guide to Kultur (1938), and dedicated his adaption of Sophocles’ Women of Trachis (1956) to him.

Among the members of the international avant-garde with whom Kitasono was in contact prior to WWII, was the poet, editor and artist Charles Henri Ford. Prior to the war Ford had contacted Kitasono about his “chain-poem” project, an international experiment in collaborative poem writing. This photograph sent by Ford was taken by his partner, the artist Pavel Tchelitchew, and was published by Kitasono in a pre-war issue of VOU.

Kitasono had close relations with the Black Mountain School, primarily through Charles Olson, the poet and its head, and Robert Creeley, the editor of Black Mountain Review, who also published (via his Mallorca-based Divers Press) Kitasono’s self-translated book Black Rain (1954). Creeley later recalled it as being, along with Olson’s Mayan Letters, the most memorable of all the works he published. Among the many praises accorded to that book, it elicited a strong letter of admiration from William Carlos Williams.

Kitasono had a rich back and forth with the poets and artists of this mid-century group, not only contributing to magazines like Black Mountain Review, but also publishing important poems and theoretical work by and about the artists and poets in VOU, including a translation of Olson’s “Projective Verse” and an introduction to the work of John Cage.

Kitasono’s cover of the Black Mountain Review utilizes one of his katto, or cuts, minimal, geometric designs in primary colors, which bear traces of Russian Constructivism as well as the Bauhaus movement, which he absorbed in the 1920s through friends like Nakada Sadanosuke. This aesthetic was among the affinities found between Kitasono and Black Mountain, which had drawn heavily from the Bauhaus’s pedagogy and structure via Josef Albers, its first head of school.

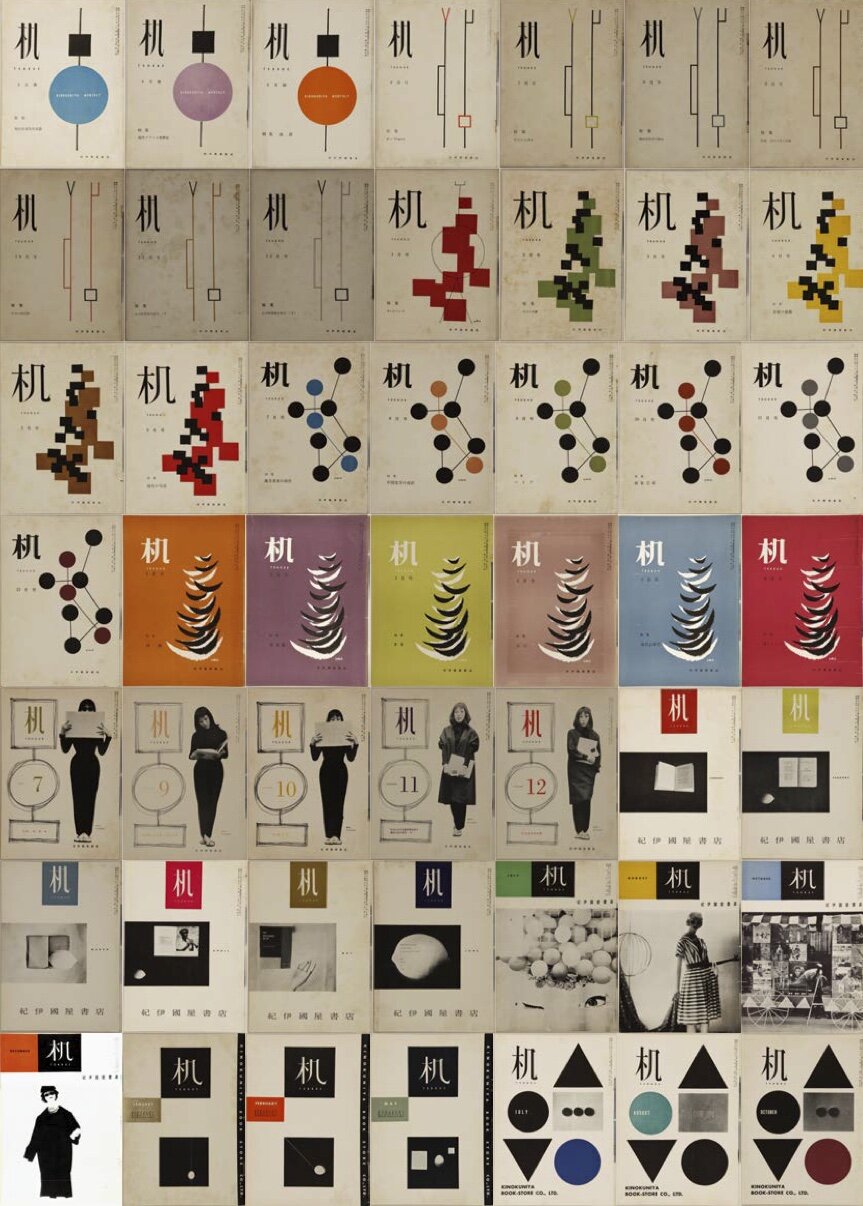

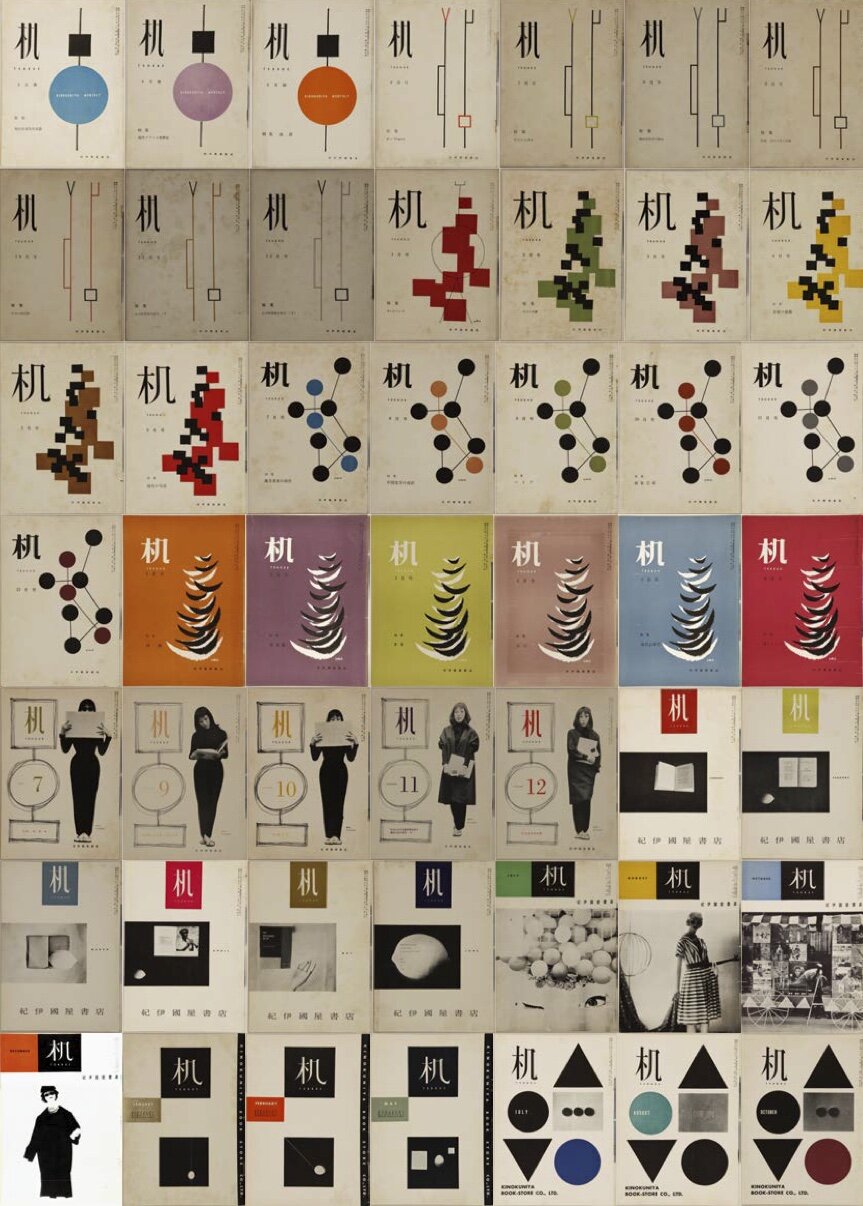

During the late 1950s Kitasono edited and designed Desk, a publication and catalog for the Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku. Desk, along with the numerous other publications Kitasono designed for commercially, forms a parallel body of work to his design for avant-garde publications, that though largely done for money, is in many ways no less experimental.

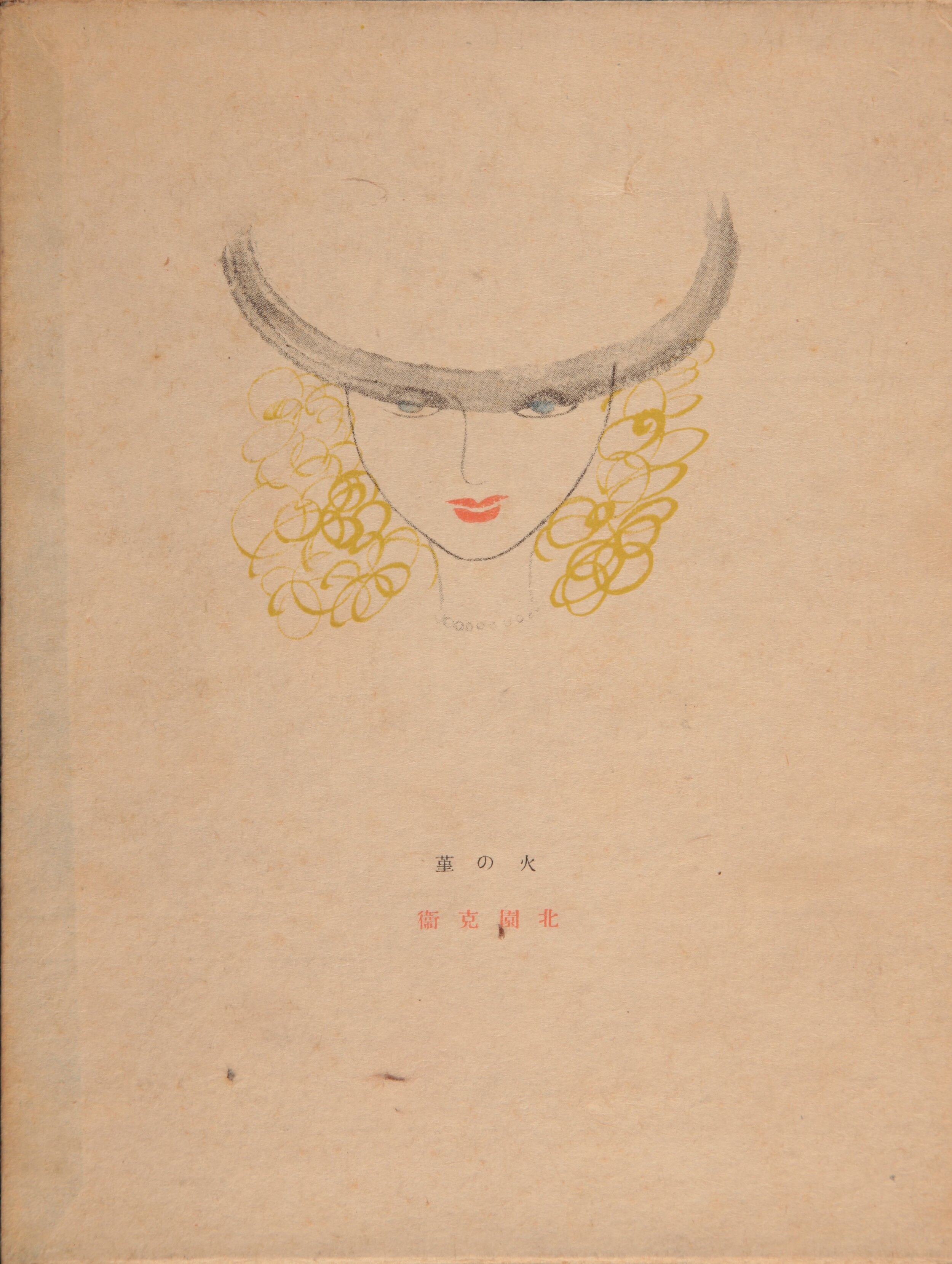

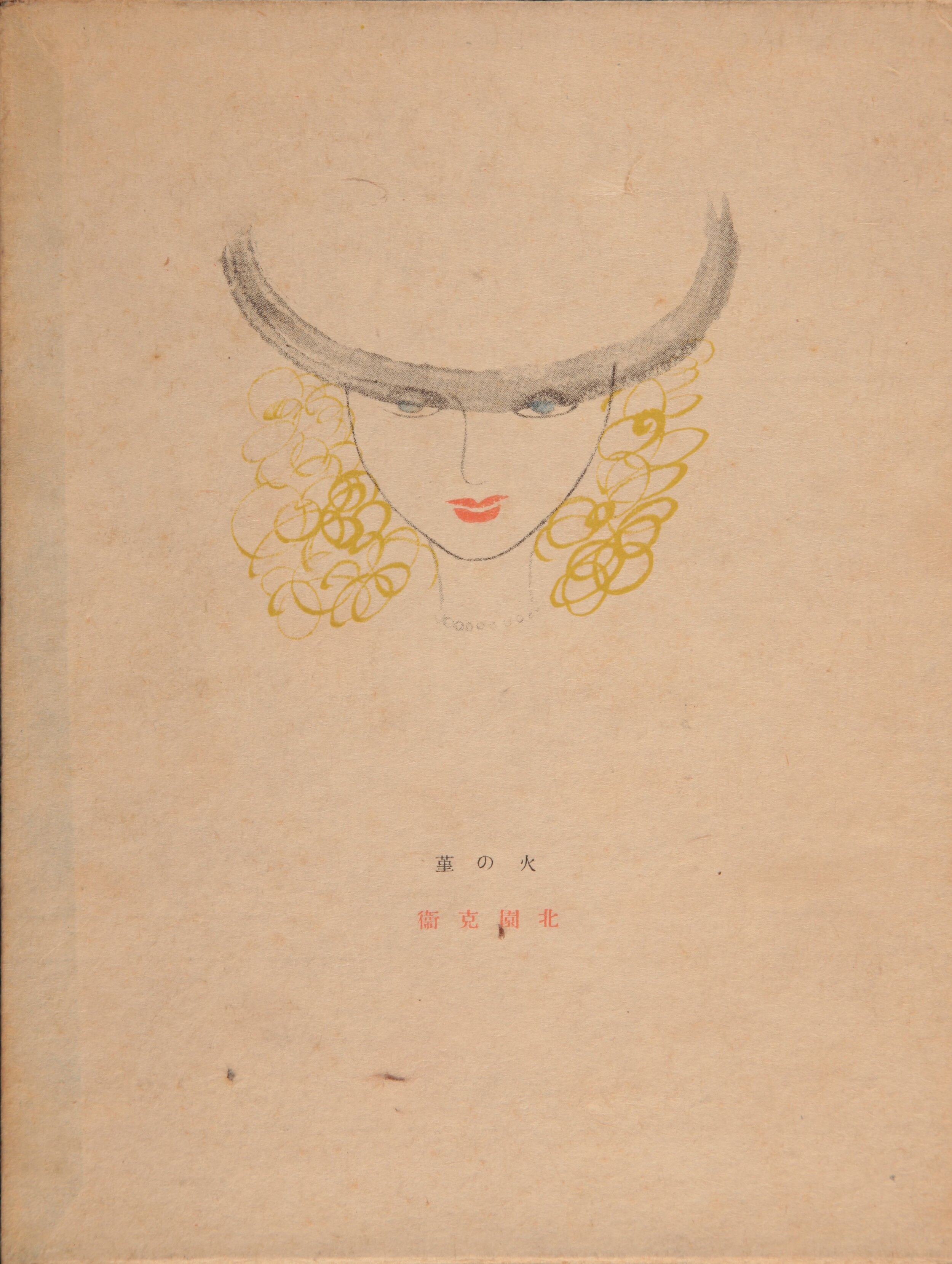

Kitasono collaborated widely with artists and designers both inside and outside of VOU, contributing his own illustrations and designs to the works of others, and working with other artists to illustrate or design his own books of poetry. The printmaker Onchi Kōshirō, for example, designed two books for Kitasono, Summer Letters (1937) and Cactus Island (1938), and the surrealist painter Tōgō Seiji illustrated the cover of Kitasono’s book Violet of Fire (1939).

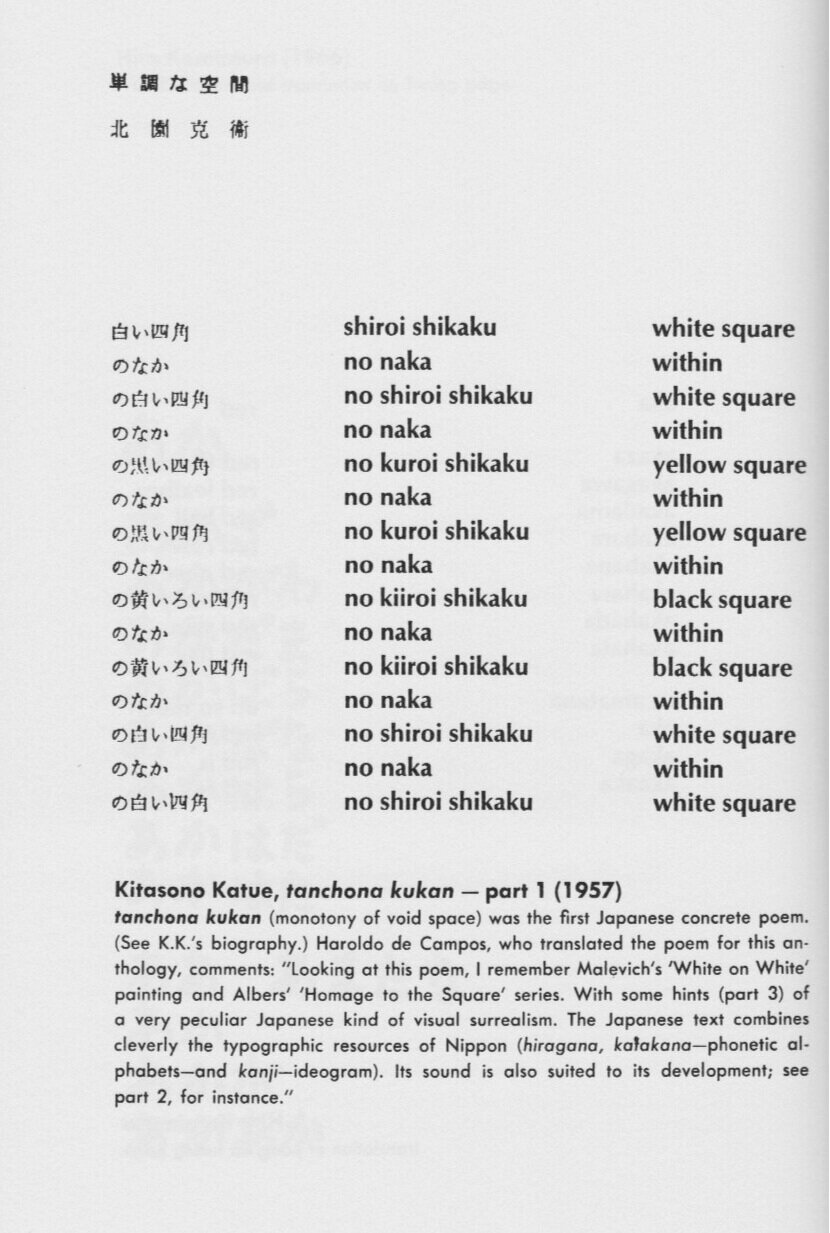

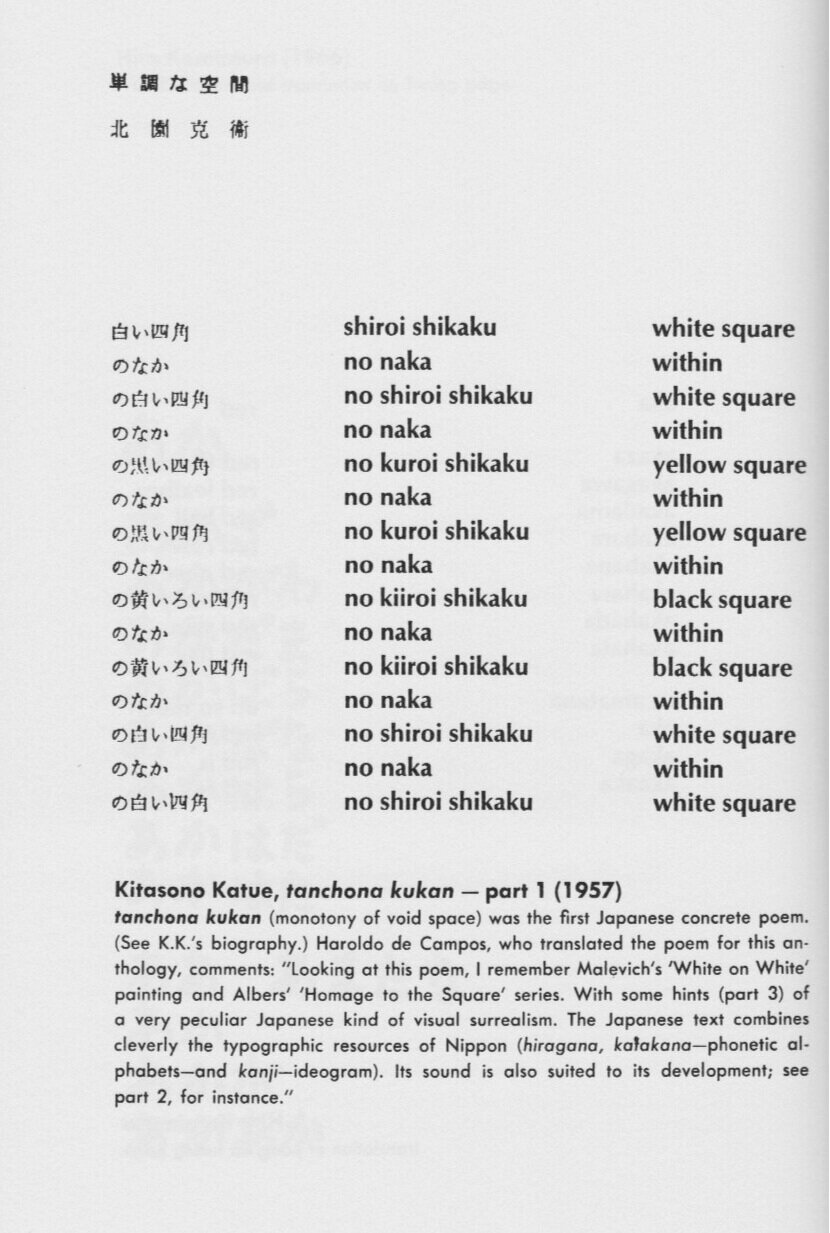

“Monotonous Space,” (here translated as “Monotony of Void Space”), was first published in VOU (1957). Subsequently translated by Haroldo de Campos, it was published in 1958 in the literary supplement of O Estado de Sao Paulo and later in the Noigandres’ magazine Invençao. It was translated into German in 1960 by Eugen Gomringer in Spirale no. 8, and finally appeared in De Campos’ english translation in Emmett Williams’ Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967). It is roughly contemporaneous, though predating similar experiments by Robert Lax, Ian Hamilton Finlay, and Carl Andre.

Partly inspired by Kazimir Malevich and Bauhaus experiments in minimalism, this work draws from a reserve of abstraction in Kitasono’s work going back to the visual repetition of poems from the late 1920s like “Magic” or the the stark, imagistic minimalism and exploration of color in works like “Semiotic Theory.” It might also be related, albeit indirectly, to the contemporaneous minimalism of painters like Ad Reinhardt or later minimalist works by musicians like Steve Reich or La Monte Young.

Though “Monotonous Space” was widely praised at the time—Kenneth Rexroth even declaring it the finest of all concrete poems—after its publication Kitasono subsequently refused to submit poems in its style when asked, sending only his photographic “plastic poems” from that point on. Ever heterodox, here as elsewhere he refused to allow his experiments to crystallize into a repetitive style.

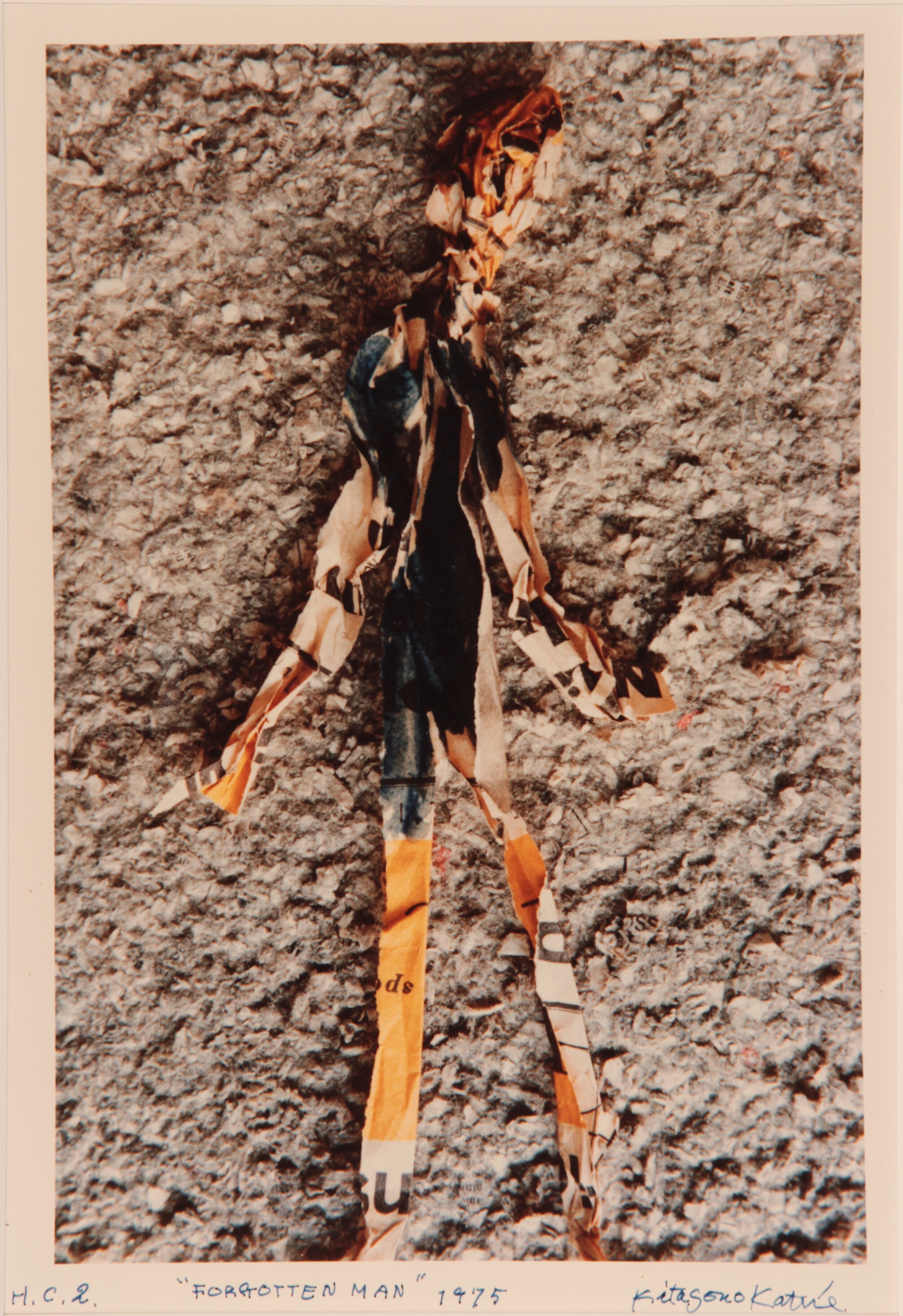

After the Second World War, Kitasono’s poetry became increasingly stark, elliptical and abstract, moving towards the margins of language until it nearly left language behind altogether. Indeed, by the late-1960s, Kitasono increasingly eschewed written poetry for his plastic poetry, which sometimes but not always included linguistic elements.

Composed mostly of assemblages or arrangements of simple objects like sticks, paper, and wire, the plastic poems both look back to the juxtapositions of surrealist collage and assemblage, and also relate to the projects of contemporaries like Ian Hamilton Finlay or Marcel Broodthaers, poets working at the intersection of text, visual art, and sculpture. There was also a rich photographic tradition within VOU itself, which by the 1970s included photographers like Torii Ryōzen, Takahashi Shōhachirō, Okazaki Katsuhiko, Hibino Fumiko, Kiyohara Etsushi, Tsuji Setsukō, Itō Motoyuki, and Kitasono’s close friend, the great surrealist photographer Yamamoto Kansuke.

Mixing elements of his poetry with an image of a stark, modernist structure, this photograph of 1956 was created during a transitional phase between Kitasono’s earlier photographic works and his later plastic poetry. It exemplifies a tendency in Kitasono’s work to combine word and image, which extends from his earliest visual poems to his last photographs.

While it might be said that poetry was primary for Kitasono, the boundaries of his idea of poetry extended far into the other arts, and in some sense he saw the separation of genres to be an illusion. As he wrote in 1965, “For us the distinction made in a previous age between poet, painter, and sculptor will disappear, and only the word artist … will remain.”

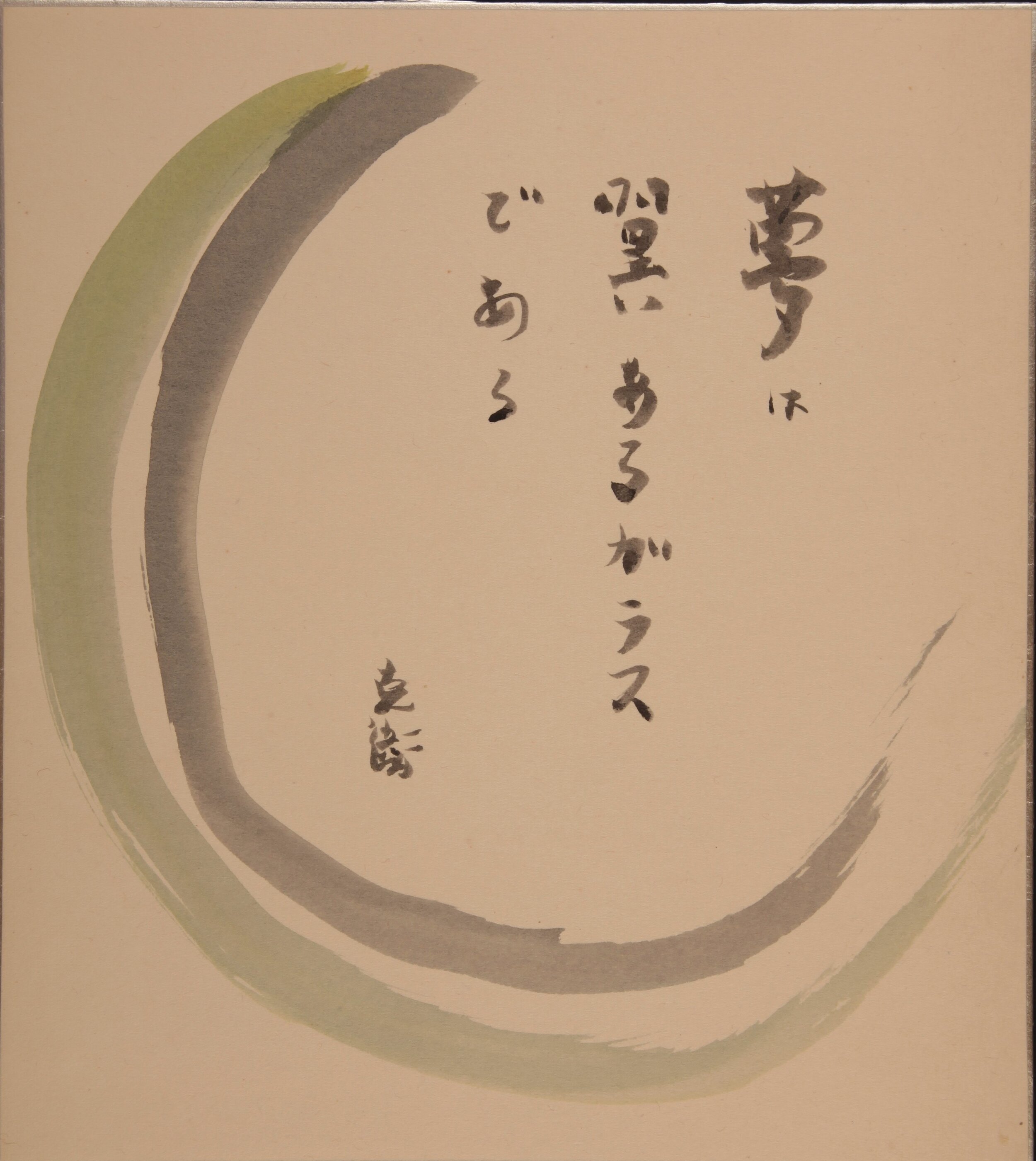

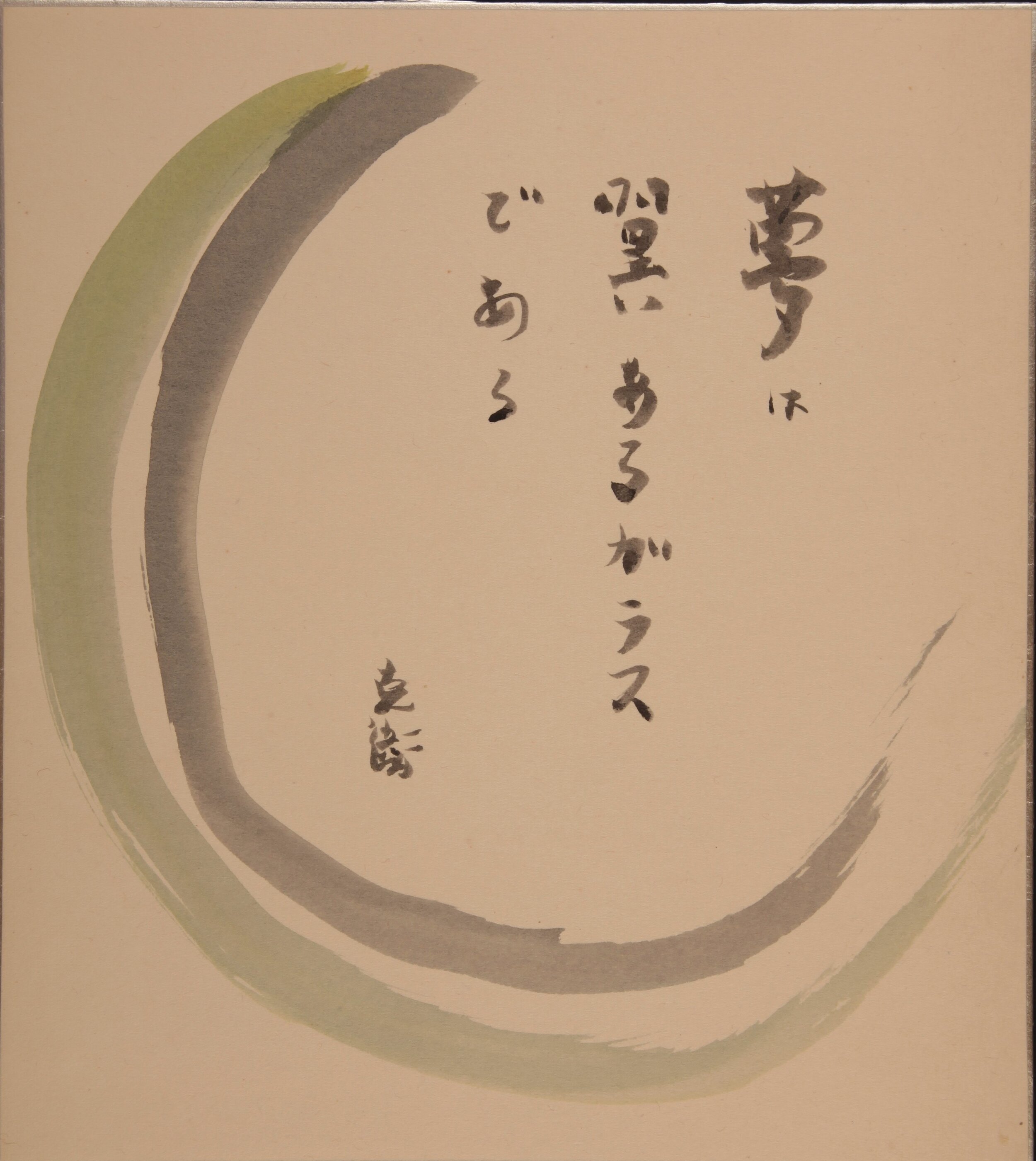

Kitasono began as a painter and, though he painted off and on, little of his work in this medium survives. What remains is mostly split between geometric abstraction, close in form to his “cuts,” and more traditional, abstract ink-painting, both of which nearly always incorporate poetry.

Containing Kitasono’s early journalistic work, this scrapbook was created in the midst of his engagement with Dada and the magazine Ge.Gjmgjgam.Prrr.Gjmgem (1924-1926). Along with collaged papers from multiple sources, including lettering from the magazine, its cover features a small photographic portrait of the poet. Though the work is of an early date, the collage’s use of mixed media, abstraction, and assemblage, as well as its engagement with multiple languages foreground themes that would occupy Kitasono throughout his whole life.

The poetry of Kitasono’s first book, Album of Whiteness (1929), while written under the influence of Dada and the nascent Japanese surrealist movement, is thoroughly unlike the avant-garde poetry common at that time either among his milieu or among the mostly French poets from which it had originated. Rather, it sets out—inspired by these movements but not limited by them—towards new procedures, forms, and usages of language.

Including diagrammatic poems (Legend of the Airship), proto-concrete poems (Magic), and poems of ironic and extreme imagistic minimalism (Semiotic Theory), the work in Album of Whiteness seems to look far-ahead to movements of the future, from visual poetry to language poetry and text-based conceptual art.

VOU magazine’s innovative formal concerns, its long life, and Kitasono’s ability to reach across culture and disciplines, made it one of the most widely known and influential non-western avant-garde magazines of the 20th century.

While there were several important avant-garde publications in Japan during the pre-war period, few were in touch directly with individuals outside Japan, and most, like MAVO and Kitasono’s own Madame Blanche or Ge.Gjmgjgam.Prrr.Gjmgem, lasted only a few years. VOU, on the other hand, starting in 1935 and ending in 1978, was the only major group and magazine to span the pre- and post-war. Additionally, it engaged directly with international artists on a large scale, facilitating translation and dialogue with nearly every major avant-garde group of that time, from the Surrealists to the Black Mountain School, Beat poets, and concrete poets.

Edited and designed by Kitasono Katue, his prints and photographic works often appeared on the covers, a small selection of which are pictured above.

A small collection of images from VOU can also be found on the plastic poetry page of this site.

Kitasono corresponded with many western artists and poets, but his most sustained engagement was with Ezra Pound, their dialogue beginning in the middle-1930s and lasting approximately three decades.

Though there were difficulties of language on either side, Kitasono and Pound’s letters served as a sounding board for their respective poetics, and are marked by mutual respect and collaborative assistance on both sides. Pound was instrumental in Kitasono and VOU’s publication in the west, and Kitasono in Pound’s publication in Japan. Pound explored Kitasono’s poetics in his influential Guide to Kultur (1938), and dedicated his adaption of Sophocles’ Women of Trachis (1956) to him.

Among the members of the international avant-garde with whom Kitasono was in contact prior to WWII, was the poet, editor and artist Charles Henri Ford. Prior to the war Ford had contacted Kitasono about his “chain-poem” project, an international experiment in collaborative poem writing. This photograph sent by Ford was taken by his partner, the artist Pavel Tchelitchew, and was published by Kitasono in a pre-war issue of VOU.

Kitasono had close relations with the Black Mountain School, primarily through Charles Olson, the poet and its head, and Robert Creeley, the editor of Black Mountain Review, who also published (via his Mallorca-based Divers Press) Kitasono’s self-translated book Black Rain (1954). Creeley later recalled it as being, along with Olson’s Mayan Letters, the most memorable of all the works he published. Among the many praises accorded to that book, it elicited a strong letter of admiration from William Carlos Williams.

Kitasono had a rich back and forth with the poets and artists of this mid-century group, not only contributing to magazines like Black Mountain Review, but also publishing important poems and theoretical work by and about the artists and poets in VOU, including a translation of Olson’s “Projective Verse” and an introduction to the work of John Cage.

Kitasono’s cover of the Black Mountain Review utilizes one of his katto, or cuts, minimal, geometric designs in primary colors, which bear traces of Russian Constructivism as well as the Bauhaus movement, which he absorbed in the 1920s through friends like Nakada Sadanosuke. This aesthetic was among the affinities found between Kitasono and Black Mountain, which had drawn heavily from the Bauhaus’s pedagogy and structure via Josef Albers, its first head of school.

During the late 1950s Kitasono edited and designed Desk, a publication and catalog for the Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku. Desk, along with the numerous other publications Kitasono designed for commercially, forms a parallel body of work to his design for avant-garde publications, that though largely done for money, is in many ways no less experimental.

Kitasono collaborated widely with artists and designers both inside and outside of VOU, contributing his own illustrations and designs to the works of others, and working with other artists to illustrate or design his own books of poetry. The printmaker Onchi Kōshirō, for example, designed two books for Kitasono, Summer Letters (1937) and Cactus Island (1938), and the surrealist painter Tōgō Seiji illustrated the cover of Kitasono’s book Violet of Fire (1939).

“Monotonous Space,” (here translated as “Monotony of Void Space”), was first published in VOU (1957). Subsequently translated by Haroldo de Campos, it was published in 1958 in the literary supplement of O Estado de Sao Paulo and later in the Noigandres’ magazine Invençao. It was translated into German in 1960 by Eugen Gomringer in Spirale no. 8, and finally appeared in De Campos’ english translation in Emmett Williams’ Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967). It is roughly contemporaneous, though predating similar experiments by Robert Lax, Ian Hamilton Finlay, and Carl Andre.

Partly inspired by Kazimir Malevich and Bauhaus experiments in minimalism, this work draws from a reserve of abstraction in Kitasono’s work going back to the visual repetition of poems from the late 1920s like “Magic” or the the stark, imagistic minimalism and exploration of color in works like “Semiotic Theory.” It might also be related, albeit indirectly, to the contemporaneous minimalism of painters like Ad Reinhardt or later minimalist works by musicians like Steve Reich or La Monte Young.

Though “Monotonous Space” was widely praised at the time—Kenneth Rexroth even declaring it the finest of all concrete poems—after its publication Kitasono subsequently refused to submit poems in its style when asked, sending only his photographic “plastic poems” from that point on. Ever heterodox, here as elsewhere he refused to allow his experiments to crystallize into a repetitive style.

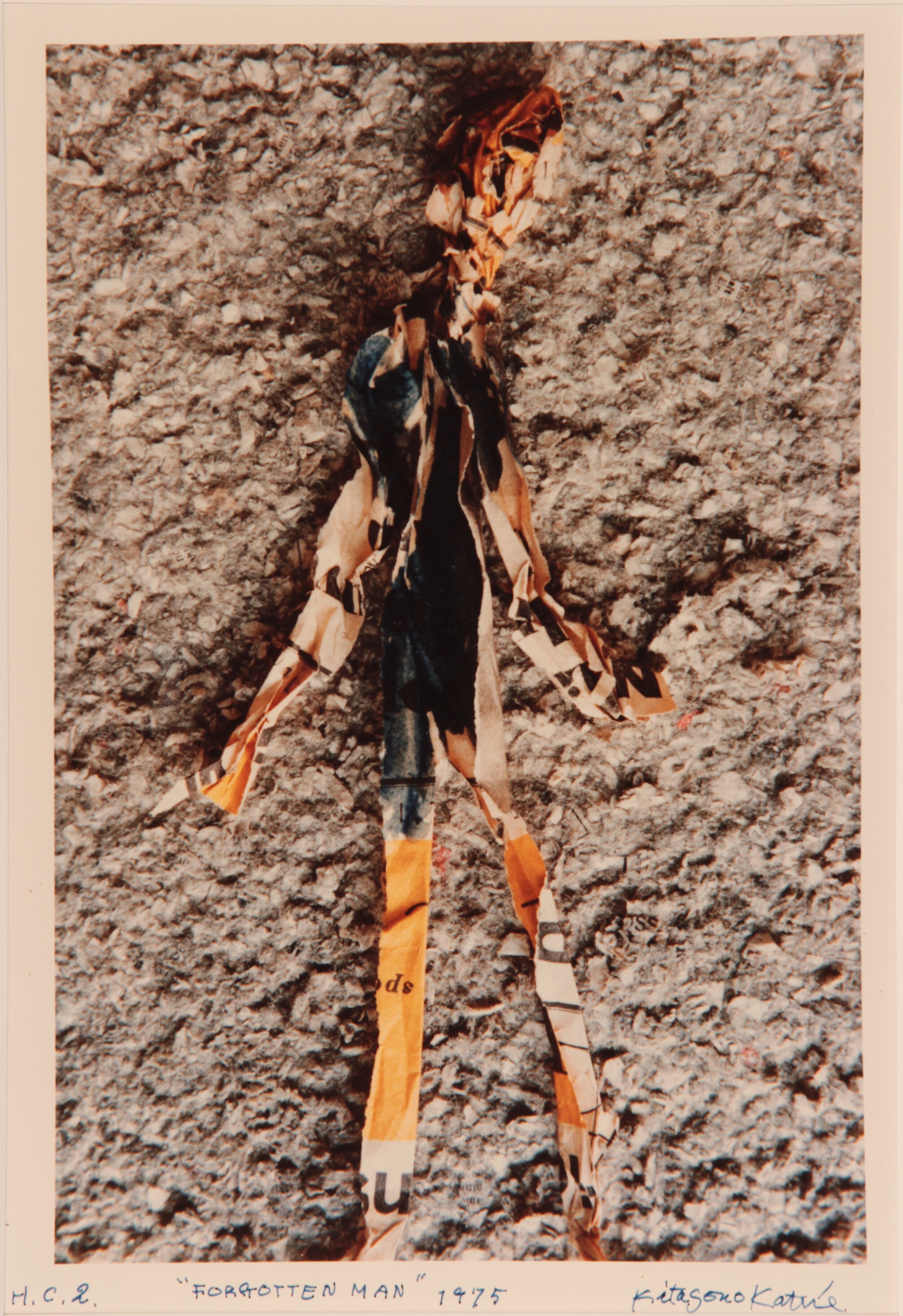

After the Second World War, Kitasono’s poetry became increasingly stark, elliptical and abstract, moving towards the margins of language until it nearly left language behind altogether. Indeed, by the late-1960s, Kitasono increasingly eschewed written poetry for his plastic poetry, which sometimes but not always included linguistic elements.

Composed mostly of assemblages or arrangements of simple objects like sticks, paper, and wire, the plastic poems both look back to the juxtapositions of surrealist collage and assemblage, and also relate to the projects of contemporaries like Ian Hamilton Finlay or Marcel Broodthaers, poets working at the intersection of text, visual art, and sculpture. There was also a rich photographic tradition within VOU itself, which by the 1970s included photographers like Torii Ryōzen, Takahashi Shōhachirō, Okazaki Katsuhiko, Hibino Fumiko, Kiyohara Etsushi, Tsuji Setsukō, Itō Motoyuki, and Kitasono’s close friend, the great surrealist photographer Yamamoto Kansuke.

Mixing elements of his poetry with an image of a stark, modernist structure, this photograph of 1956 was created during a transitional phase between Kitasono’s earlier photographic works and his later plastic poetry. It exemplifies a tendency in Kitasono’s work to combine word and image, which extends from his earliest visual poems to his last photographs.

While it might be said that poetry was primary for Kitasono, the boundaries of his idea of poetry extended far into the other arts, and in some sense he saw the separation of genres to be an illusion. As he wrote in 1965, “For us the distinction made in a previous age between poet, painter, and sculptor will disappear, and only the word artist … will remain.”

Kitasono began as a painter and, though he painted off and on, little of his work in this medium survives. What remains is mostly split between geometric abstraction, close in form to his “cuts,” and more traditional, abstract ink-painting, both of which nearly always incorporate poetry.